Connor Smyth

Growing in Excess and Other Problems of Modern Agriculture

Last year I went camping with my Dad and we visited his childhood friend who now lives in the Niagara region of Ontario, Canada. We had moved the topic of conversation towards Niagara’s wine production when he told me something that surprised me. Niagara is known for growing many things including, at one point, peaches. But now, the wine industry has taken over a large part of Niagara meaning the diversity in what is grown is significantly less than it once was. His statement stuck with me though and led me to an important question, “are we growing the right things?”.

After a bit of research, I discovered he was right; Niagara used to grow peaches of all things. [1] Niagara is obviously well equipped to grow many things including peaches, corn, beans, and more, but is it best for growing wine? I wanted to figure out what type of climates were best for growing wine. In Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, he mentioned some research on what climates produce the best wine. The summary of that research is that the best wine is produced with warm and dry summers and generally wet springs.[2]

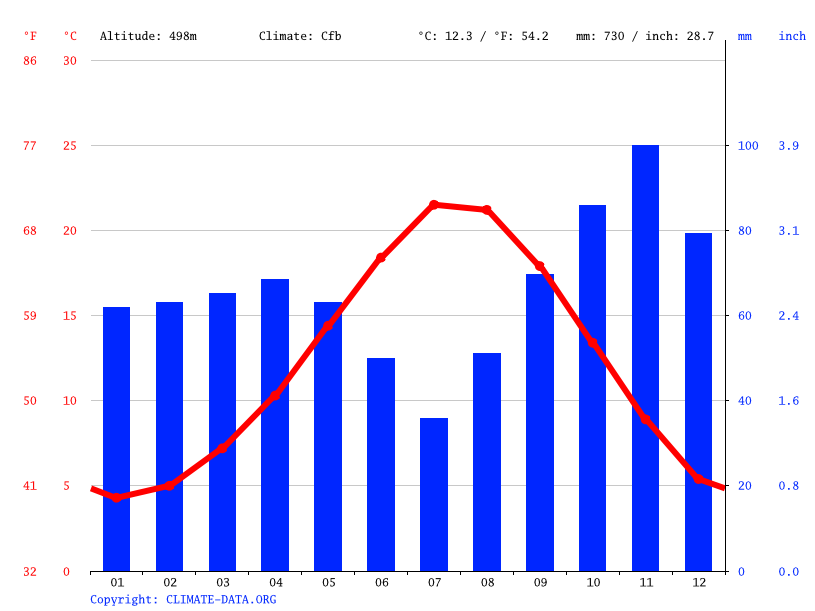

I knew that a major wine region in Italy is Tuscany and one of the major producers of wine there is Montepulciano. If we look at the precipitation and temperature data for the city, we can see that it has moderately wet springs, and warm and dry summers. A recipe for wine success.

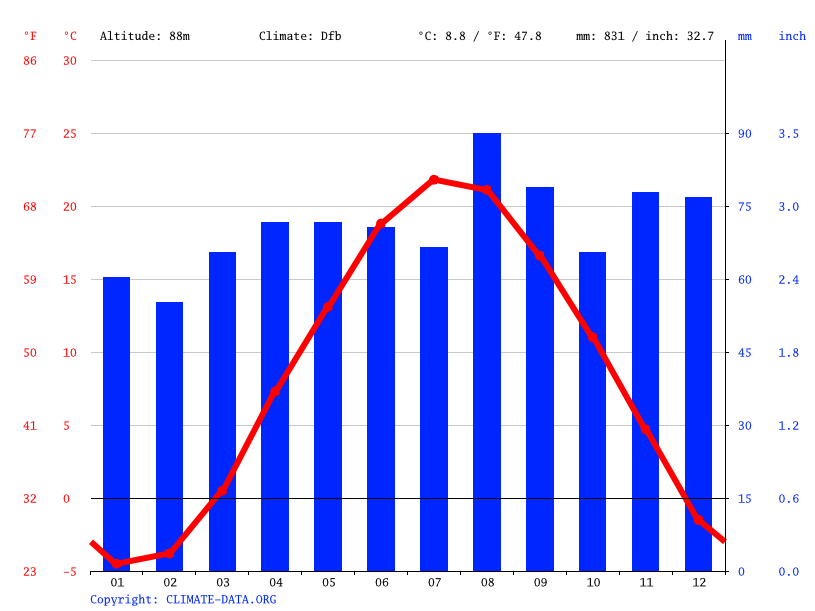

If we compare this data with the Niagara region data, we can see that while the temperatures level off at the similar points in the summer, Niagara has a very wet climate all year round.

Based on this data we can likely conclude that Niagara is growing food sub-optimally. The impacts of growing agriculture “incorrectly”, that is growing one type of crop such wine grapes when a more suitable crop such as peaches would be better suited, are less so in North America as compared to countries suffering from malnourishment. Vaclav Smil points out in his book, Harvesting the Biosphere, that humans waste anywhere from 25%-45% of their food production. The United States produces about 3700 kcal per person per day, but the average American adult only consumes about 2100 kcal per day. This is 1600 kcal wasted per person per day, which means the United States wastes about 40% of its food production. To put it in simpler terms this would be like throwing out five McDonalds cheeseburgers per person per day, every day.[5]

He also points out that we produce enough food currently to feed about 10 billion people on our currently populated 7.6-billion-person Earth. We have clearly solved the problem of creating enough food to feed everyone then, right? Well if that were true then malnourishment should have been eradicated, but it’s not. We may have technically figured out how to produce enough food, but we have no method to distribute our current overproduction of food to the people who need it most. This poor lack of distribution starts from the very bottom with farmers and then the next level of restaurants, but it is in no way their fault. They do not have the incentives or capabilities to distribute this excess food.

Ask any person who works in a restaurant and they will tell you that in many places laws make it extremely difficult to give their excess food to places like homeless shelters.[6] If we take a look at farmers, then we see that they neither have the subsidies required for them to survive if they were to set aside a portion of their production to distribute to those in need, nor do they have the infrastructure to actually separate that food, store it, and distribute it.

Even if these problems were solved, we would still only be solving the problem locally since it would be next to impossible and extremely costly to distribute all of the excess food on a global scale. In the United States, the estimated prevalence of undernourishment by the World Bank is about 3% of the population.[7] With a population total of 328.2 million [8] it means that 9 900 000 suffer from malnourishment. If we fed everyone appropriately in the U.S. with the excess food they have then that would mean that the united states has reduced its excess food percentage to 37%. Or in other words we have reduced the excess food production from 5 McDonalds cheeseburgers per person per day, every day, to 4.625 McDonalds cheeseburgers per person per day, every day. It is a great improvement for those malnourished in America but has no effect on the other 810 252 000 malnourished people on Earth.[7]

We can see that we have already answered the question of “how do we make enough food for everyone on Earth?”. So much so that we have figured out how to grow enough food to feed another 2.5 billion people. We can also see that it is not feasible to try to share the excess food on a global scale due to physical and economic constraints. This leads us to ask a new question, “how do we feed everyone equitably?”. The answer is actually really not that difficult. We need to share our agricultural knowledge and technologies which enables them to be self-sufficient and solve their own malnourishment problems. Not only will this benefit the people, but it will also benefit those peoples’ economies, further boosting them on the world economic stage.

Let’s look at China as a first example. In the past quarter-century China has lifted more than 500 million people out of extreme poverty.[9] They did all this by investing in human capital, which is the economic value of a person’s experience and skills. This includes assets like education, training, intelligence, skills, and health.[10] Another example is India, where nearly 100 million people have risen above the poverty line in just over a decade. India had a very meager wheat yield, but due to the introduction of modern agricultural innovations that production has almost quadrupled.[11]

We can use these same techniques and introduce them to places where we expect to see extreme poverty become most prevalent in the next 30 years. It’s estimated that without intervention, by the year 2050, 90% of people living in extreme poverty will be living in Sub-Saharan Africa. By introducing these technologies, such as fertilization, pasteurization, soil maps, we can begin to determine how to grow food there as effectively and as efficiently as we do in North America. Perhaps so effectively that they can have the liberty to grow sub-optimally like they do in the Niagara region of Ontario, Canada.

What this means for us who live in countries that are privileged enough to have already “figured it all out”, is that we need to put our efforts towards the sharing of knowledge. We need to freely share our knowledge and technologies with others and other countries that could benefit greatly from pulling people out of extreme poverty and eradicating malnourishment. Don’t let economists confuse you into thinking that our goal is to grow as much as we can. We cannot have indefinite growth on a finite planet, sorry.

I will leave with a parting thought; share knowledge, share technologies, and help one another. Do not ask for anything in return, help people for the betterment of all mankind. We only have one planet and we are all on it. If we continue with this closed-off, non-sharing mindset that capitalism seems to promote, then in the end we all lose.

- https://memoriesofniagara.wordpress.com/agriculture/

- https://www.amazon.com/Thinking-Fast-Slow-Daniel-Kahneman/dp/0374533555

- https://en.climate-data.org/europe/italy/tuscany/montepulciano-13284/#climate-graph

- https://en.climate-data.org/north-america/canada/ontario/niagara-on-the-lake-717712/#climate-graph

- https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/harvesting-biosphere

- https://universe.byu.edu/2017/11/27/confusion-abounds-over-how-to-make-food-donations-in-utah-1/

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SN.ITK.DEFC.ZS

- https://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=kf7tgg1uo9ude_&met_y=population&idim=country:US&hl=en&dl=en

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.DDAY?locations=CN

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/humancapital.asp

- https://youtu.be/efnHiz0USQE